But plugging in a modern colloquialism isn't best either.

Why?

What's the difference between a "modern colloquialism" and any other aspect of modern language?

The answer to that question is NOTHING! "Modern colloquialism" is just the term you're assigning a certain set of sounds we use to communicate a particular idea that you don't want for the bible to be communicating. I don't care at all whether or not the idea is communicated via a whole sentence, a modern figure of speech, a modern colloquialism, or a single word so long as the concept is being communicated accurately.

In short, there isn't anything about a "modern colloquialism" in and of itself that renders a translation invalid.

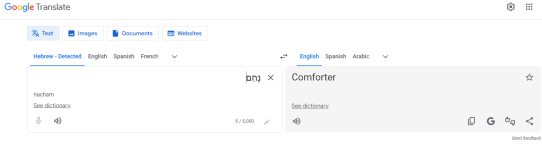

We'd instead follow: Nacham means to sigh.

Except that that isn't what it means, Lon!

When we think of circumstances that cause One to sigh, we see that it can be from frustration, from a forseen perhaps inevitable outcome.

Right and that isn't what is happening in any biblical example you care to discuss. The word means to change one's thinking, to alter one's state of mind.

Further, how would it help you even if it did mean to be frustrated? Can an immutable God be frustrated in your doctrine? How does that work exactly?

"Sighing" is a legitimate word.

Of course it is but it isn't what is being communicated in any of the 108 times it is used in scripture.

This is NOT my opinion. You don't get to show up here and try to tell us all that multiple millennia worth of bible translation has been done in error and that you've discovered the actual meaning of the word Nacham. You haven't. You ARE wrong.

There has never been a standard Bible translation in any language that renders any occurrence of the Hebrew נָחַם (nacham) simply as “to sigh.”

In all major English translations (KJV, NKJV, NASB, ESV, NIV, etc.):

Nacham is consistently translated as:

- “repent”

- “relent”

- “be sorry”

- “have compassion”

- “be comforted”

Even in the most literal translations (like Young’s Literal Translation or the NASB), “sigh” never appears as the rendering of nacham in any verse.

In the Septuagint (LXX – Greek Translation of the OT), Nacham is generally rendered using words like:

- μετανοέω (metanoeō – to repent/change mind)

- παρακαλέω (parakaleō – to comfort or console)

Again, never as a Greek verb that corresponds simply to “sigh” (like στενάζω, which would mean to groan or sigh).

In other languages such as Latin, German, French, Spanish, etc.....

- In the Vulgate (Latin): nacham is translated as paenitere (to repent) or consolari (to be comforted).

- In Luther’s German Bible and most modern German translations: it’s rendered as “reuen” (to regret) or “trösten” (to comfort).

- In Spanish, “arrepentirse” (to repent) or “consolar” (to comfort).

- In French, “regretter” (to regret), “se repentir” (to repent), or “consoler” (to comfort).

None use the equivalent of “sigh” in any verse where nacham appears. EVER!

We don't have to 'guess' what One sighs for, just note that the word is "God sighed." That works. The 'why' is where English nearly shoves an Open narrative. If our theology is pushed by translation, we might not be blamed, not our fault, really, for believing what an English translator thought Such is why I love Open Theists, I believe I see the mistake, but I think it an honest one. The consistency, if obvious, is seen down the road and it most often has to do with what a translator wrote. Forgive me for audacity, but let me explain it: When I was taking Greek, I had to translate passages. I'm a literalist so go for minimum interference when writing from Greek to English. There were times I thought I translated much better. I asked my prof, Dr. Koivisto, and he said that the reason for translation difference is explained by committee. Thomas Nelson took 200 scholars, some language experts, some English, and had them work on a passage until there was consensus, or the English scholars won, based on 'best English conveyance.' What it meant, was, that Dr. Koivisto would have (did) translate exactly (better) than I had, but publishers went with what they wanted over that. If the NIV says "Changed His mind" it is not because of Greek, nor Greek translation.

The problem isn't that translators are inserting Open Theism into the Bible, Lon! The problem is that the text itself says what it says. Whether it's Hebrew nacham or Greek metanoeō, the consistent usage across Scripture conveys emotional movement, regret, sorrow, compassion, even reversal. That’s not an English committee problem. That’s what the original words actually mean in context. No translator came along and shoved "changed His mind" into the text because they were pushing Open Theism. On the contrary, virtually all modern English translations were translated by Calvinists and looked for reasons to soften the translation into English. That's why the NIV, says "relent" in Jeremiah 18, for example, instead of the more accurate "repent" that the KJV uses. It's the same tactic you are using just to a lesser degree.

The idea that we should translate

nacham as merely "sighed" to avoid theological discomfort turns translation into theology by manipulation. It’s the exact thing being accused, just in reverse. You don't get to flatten the meaning of a word just because you don’t like where it leads. The Calvinists stepped on Nacham a bit to render it "relent", you want to flatten it entirely and make it mean something entirely unrelated to what the original intent was.

Translation must reflect language (i.e. grammar, syntax, usage, context), not doctrinal preference. If the text makes you uncomfortable, that’s a signal to reexamine your theology, not to rewrite the vocabulary. Let the text speak. Then do the hard work of building doctrine on what it actually says, not what you wish it said.

For me, the colloquial is the error.

No one cares what the error is "for you", Lon. The bible isn't your personal play thing. It isn't a set of Lego blocks where you're allowed to build your own version of the Millennium Falcon with extra gun turrets and half as much engine if you so desire.

While I understand "I feel you" it is, in fact, much clearer to say "I empathize, I understand sympathetically what you are saying." If an idea conveys a problem, like touching another person, we want to clear that up before we translate to another language empathy, sympathy, and mutuality before 'feel' pushes the narrative too far removed from intent. Such is where 'to sigh' is important.

Which is absolutely an issue with 'translation.' Hebrew simply means 'to sigh.' Rather, context tells us 'why.' If we translated consistently, we'd leave it to the reader to infer/figure out, why God sighed. It is 'translated' as 'comforted, stopped, or quit' (Hebrew concordance).

Sigh (English) can mean regret, grief, chose differently, etc., but these are derived from the idea of 'sighing/why did He sigh?'

Sorry, Lon! "Nacham" DOES NOT mean "to sigh". Never has, never will.

You are making reference to the words etymology, not it's meaning, not the concept that the word gives name to. It is common for words, especially Semitic languages to have a connection to physical actions associated with a particular concept. An emotional response is often accompanied by a deep breath, for example. And so a word associated with a particular action might have its origin in the sound people make when performing that action. Thus, "nacham" MIGHT have become a word because of some such thing.

There are two impotant points here...

1. Even if "nacham" was a sigh that, over time, turned into a word, it doesn't mean that the word means "to sigh". The word refers to whatever concept was associated with that sigh.

2. NO ONE KNOWS that this "to sigh" idea was the real origin of the word "nacham" It's a theory - at best!

Which we have done together, to a fruitful affect.

We have to interpret, but we must always evaluate if we have done so correctly. You and I have done this, in discussion, to a good effect. We may not agree, but the fact that we've done it is a very good process and forces us to ensure we are understanding a passage correctly. It is a good thing. For me, the most basic is bankable. We can count on it. What is derivative isn't as secure. Bad? Sometimes, but if we really work on how well we understand conveyance in its most basic form, we do very well. Honestly, I'd not have many people do this with me (not bragging, just saying most don't 'like' to dig into language and minutia). I know you are up to, and desirous of this kind of analysis.

It is true that translation is not purely mechanical. Language is not math. Translators must often weigh multiple meanings and choose the one that best fits the grammar, syntax, and context of the passage. Interpretation is, to some degree, unavoidable. No serious person denies that.

However, that is a far cry from saying that translators are free to massage a word’s meaning in order to protect a theological system. Interpretation becomes abuse the moment a translator filters the text through doctrinal preference rather than linguistic usage. The responsibility of the translator is to render what the author actually said, not what the translator wishes had been said.

In the case of "nacham", the idea that it “really just means to sigh” is not cautious interpretation, it's theological imposition. The word does not mean to sigh. It just doesn't. That is not how it is defined in any Hebrew lexicon, and it is not how it is used in Scripture - ever!. The word reflects emotional or volitional movement (i.e. regret, sorrow, compassion, comfort, or change of mind), depending on the context. That is not the translator’s opinion. That is how the word functions, these are the concepts that the word names in the Hebrew language.

Reducing nacham to “sigh” in order to sidestep the theological tension of God regretting or repenting is not honest translation. It is a deliberate retreat from the text. The translator who sees tension and preserves it is doing his job. The one who erases that tension in order to make God more palatable has left the work of translation behind and entered the realm of commentary or even outright revision.

Translation involves interpretation, yes, but it does not permit invention. The difference being one of motive. The proper sort of interpretation in translation is linguistic, not theological.

If you followed (and I believe you have), I'd like to revisit this closing statement. For me, it is yet premature to a consensus of accepted terms on point. I want to say, once again, I agree with you I'm analytical ad nauseum, appreciate when you walk down that road, but it may be a bit too off-topic here. I was rereading and realize this is a 'how to answer' thread where I'm possibly out of place, other than being one of the ones where it is ultimately directed. In Him -Lon

I'm not sure how much more of a concencus you think there can be on this point, Lon. Show me even one single translation of the bible in any language in all of the hundreds of Old Testament translations that have been done of the centuries where Nacham has ever been translated as "to sigh" or it's equivalent in some other language. Even if you somehow produced one, which you won't do because they it doesn't exist, that would be a weird outlier of a translation that was so oddly unique as to be flatly false and it would certainly be the absolute opposite of concencus!

This is really what you need to do, Lon. And I'm serious about this....

You need to put that analytical mind of yours to work on the question....

"What would motivate me (Lon) to look so hard for a reason to render a common, well understood, Hebrew word to mean something so obscure that I can make it mean anything at all?"

That's what you're doing here, Lon. You grasping at straws that don't even qualify as actual straws. "Nacham" DOES NOT mean "sigh". No translator or lexicon has ever rendered it in that way. So why would you show up here trying to insist that this is what it means? Where's the motive? What would it cost you to simply accept that it means what it obviously does mean?

I mean, when the bible tells you to repent from sin, are you really going to sit there and tell me that you sighed about it and so God forgave you because you took a deep breath and felt an emotion related to it? Do you really believe that Job simply sighed in Job 42:6? Was Ezekiel calling on Israel to perform one big communal breathing exercise in Ezekiel 14:6? Come on now!